A Diplomatic Odyssey: Soft Power and Women in the Moonshot Era

by Saakshi Kale

When you imagine spaceflight, do you envision a spacecraft propelled beyond the atmosphere or a journey to global superiority? How do you see the astronauts — in silver spacesuits aboard that spacecraft, or in formal suits in a palace in Warsaw? And their families — their wives, in particular — do they feature as side characters, or as protagonists?

In John F. Kennedy Jr.’s vision, the space race transcended technological goals of innovation and futurism and symbolized global political dominance and prestige. From the beginning of his presidency in 1961, the National Aeronautics and Space Agency’s (NASA) ‘Moonshot’ era posed American competition to the Soviets’ successes in human spaceflight. That year, the Soviets had already launched cosmonaut Yuri Gargarin in the first ever manned space orbit. For Kennedy, “much depended on the United States going to the moon, beating the Soviet Union, being first, winning the Cold War in the name of democracy and freedom, and planting the American flag on the lunar surface” (Brinkley 2019:xii; emphasis added). He viewed the astronauts of Project Mercury, NASA’s first human spaceflight mission, to be “ultimately fearless public servants” (Brinkley 2019:xviii). The Moonshot era transformed spaceflight into a tactical diplomatic mission championing American democracy over Society communism; astronauts into informal agents of foreign relations; and their wives into the defining cultural and domestic elements which accentuated the ‘soft power’ of space diplomacy.

The ‘soft power’ concept was popularized in the late Cold War era. It refers to non-military political influence in international affairs, typically by using social and cultural resources and products to foster political change and relationships (Gallarotti 2011; Rothman 2011). These resources spanned everything from art and music to portrayals of domestic life — life at home and at work, houseware, hobbies (Rogers-Cooper 2015). In the democracy vs. communism conflict of the Cold War, soft power was an effective tool to convert ideologies without military intervention (Rothman 2011).

Spaceflight and the astronauts were packaged into this matrix of diplomatic commodities by Richard Nixon, during his term as President after Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. Nixon embarked on a diplomatic tour right after the return of Apollo 11, the first manned spacecraft to land on the moon. On this tour, he leveraged the outpouring of congratulations to meet with the evasive North Vietnamese leadership and discuss resolving the Vietnam War, plant American presence in Romania amidst the Cold War, and reinforce a New Asia policy in Pakistan and the Philippines (Muir-Harmony 2020). He also thanked astronauts Neil Armstrong, Edwin Aldrin, and Michael Collins for “their role in making the world united,” indicating that Apollo 11 was not just a scientific achievement, but a social and global bridge toward lofty humanitarian goals such as peace on Earth and discrete foreign policy goals such as developing respectful relationships (Muir-Harmony 2020:225). The Apollo 11 astronauts embarked on a presidential goodwill tour of their own, called Giantstep, to develop relationships with emerging powers. They visited Lebanon, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and India, to solidify American recognition of potential Arab, African, and Asian allies (Muir-Harmony 2020).

Two years later, the crew of Apollo 15 — Commander David R. Scott, Lunar Module Pilot James B. Irwin, and Command Module Pilot Alfred M. Worden — embarked on a similar goodwill tour to Western Europe, Poland, and Yugoslavia. The Apollo 15 tour to Poland and Yugoslavia is particularly relevant to studies of American soft power diplomacy in the Cold War era, as Poland was a part of the Soviet Union, and Yugoslavia was a powerful member of the Non-Aligned Movement. Ostensibly, the tour aimed to kickstart scientific and technological discourse on lunar exploration, rather than “parades and civic affairs” (Scott 1972a:1). Yet, it was orchestrated to immerse both parties — the Americans and their hosts — in political and sociocultural exchange.

The Apollo 15 astronauts arrived to an official reception in Poland, featuring, among others, Prof. Trzebiatowski, the President of the Polish Academy of Science, and Walter J. Stoessel Jr., the U.S. ambassador to Poland.

In another photograph, Al Worden and David Scott stand in the Palace of Culture and Science in Warsaw, Poland. An article in The Guardian declared that there “has been no more pivotal a building constructed in Poland after 1945” (Pyzik 2015). The sculptures of Polish heroes, including astronomer Copernicus, Romantic poet Adam Mickiewicz, and physicist Marie Curie, bring together science and culture, two conventionally dichotomized disciplines.

Demonstrating the more scientific half of this cultural expedition, another candid picture shows Scott, Worden, and Irwin in front of the Nicolaus Copernicus monument in Warsaw.

The astronauts also had drinks with Branko Pesic, the Mayor of Belgrade; spoke with dignitaries at the Mayor’s Palace in Ljubljana; and participated in a fox hunting trip in Belgrade. In a picture from the fox hunt, Worden and Scott pose with Slavko Sutlovic, a member of Yugoslavia’s Federal Administration for International Scientific, Educational, Cultural and Technical Cooperation. Not only is fox hunting a time-honored tradition in Yugoslav and Serbian culture, hunting in itself has been instrumentalized as a form of alliance-building. The Soviets adopted ‘hunting as diplomacy’ from Yugoslavia, posing it as a strategic performance of masculinity to “shape new and reaffirm faltering alliances” (Bakhmetyeva 2022:269).

Many of these photos are dominantly masculine. In a form of contrast, a series of photographs shows David Scott and his wife Lurton Scott skiing with other dignitaries in Zagreb. Mountainous sports were a cornerstone of US-Soviet diplomacy during the 1970s and 80s, reshaping local landscapes and customs into arenas for engagement and partnership (Flynn 2024).

The astronauts’ wives accompanying them also highlights the tour’s diplomatic nature and propagation of domestic values. Masculinity doesn’t fully constitute ‘soft power.’ The first American woman to hold a major diplomatic post, Clare Boothe Luce — appointed Ambassador to Italy in 1953 — wrote that “diplomacy is a feminine art” (Morin 1994:27). In the shifting ideological landscape of the Cold War, diplomats’ wives fleshed out the more ‘feminine’ and ‘domestic’ aspects of the diplomatic palette (Towns 2020). Their unrecognized labor included “representational entertaining and advocacy; […] and cultural diplomacy” (Penler 2023:7). The ‘soft’ nature of these initiatives gets further softened by the wives’ performance of “sociability in diplomacy” (Shimazu 2014:34), referring to their “people-to-people” engagement and reproduction of American friendliness and hospitality (Penler 2023:14). Behind these performances, these women also gathered local knowledge and information, a task which had become a pillar of American diplomacy by the 1950s (Penler 2023).

Likewise, the Apollo 15 astronauts’ wives were never ornamental. Their soft launch as instruments of public service occurred early. In a letter addressed to David Scott, Ben Gillespie, then-Manager of Public Affairs at NASA, thanked Lurton Scott for speaking at the Annual Meeting of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. This meeting was conducted in late 1967, almost 4 years prior to the Apollo 15 mission. In a picture, Lurton Scott speaks to yet another audience, this time during the Apollo 15 crew’s visit to the Panama Canal in early 1970 to open the Regional Olympics. On the Poland and Yugoslavia tour, the women are often photographed together, separate from the men, fulfilling the cultural half of their husbands’ scientific missions. In the counterpart to the picture of David Scott speaking with Ambassador Stoessel, Lurton Scott is pictured with Mrs. Stuessel and Mary Irwin, wife of James Irwin, selecting Polish folk costumes.

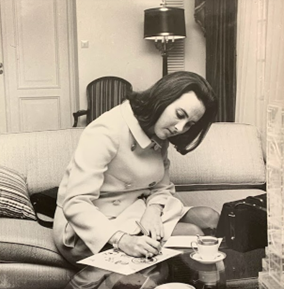

Another picture shows Lurton Scott autographing pictures at the Stoessels’ residence.

In pictures from the Wilanow Palace in Warsaw, Lurton Scott stands with other women, smiling up at the embossed ceiling. In another picture from the Warsaw outing where the astronauts stood by the Nicolaus Copernicus monument, Lurton Scott is pictured walking in the Old Market Square, accompanied by women from the American Embassy in Warsaw.

However, the wives’ duties were not confined to the purely social or the purely cultural; their engagements were politically underlined as well. For instance, they met and viewed artworks by Ivan Lacković, a famous Croatian landscape artist. Lacković was also politically active, and was one of the founding members of the Croatian Democratic Union, an anti-Yugoslavian party which came to power after Croatia won independence. In another women-only picture, Lurton Scott sits with Mrs. Johnson, the wife of American Charge d’Affaires Richard E. Johnson, and Mrs. Jakovlevski, the wife of Trpe Jakovlevski. They were attending a reception hosted by Jakovlevski, who at the time was a member of the Federal Executive Council of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

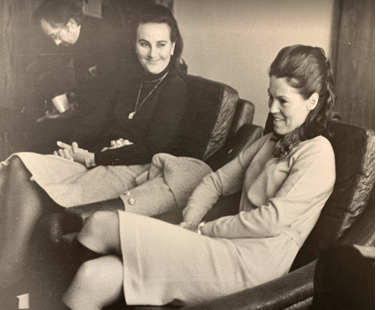

In Zagreb, Lurton Scott and Mary Irwin are pictured speaking at a press conference at the Hotel International. They sit smiling, seemingly at ease with the unprecedented demands of their new positions.

So, where does our odyssey with the Apollo 15 astronauts and their wives leave us? These photos, and the stories they tell, transform spaceflight and astronauts from politically-neutral to politicized endeavors and agents. Spaceflight is both to the moon and toward global dominance, and astronauts don spacesuits as well as formal suits. Although they did not march in any parades, they were ensconced in contemporary international affairs, projecting the progress that could be achieved by practicing American values. In the backdrop of Nixon’s soft power strategy during the Cold War, the Apollo 15 tour enabled Soviet and Non-Aligned citizens, scientists, and policymakers alike to interact with American culture.

In the cultural dimension of the tour, the astronauts’ wives acted as protagonists. Yet, their presence is neglected in textual records. In NASA’s account of the Apollo 15 crew’s post-mission activities, the wives appear briefly, in the periphery (Uri 2021). In a speech in 1972, Lurton Scott said, “We’ve had two of the Russian cosmonauts to dinner in our home. We entertained the British ambassador for lunch one day, which really threw me, trying to get lunch ready for the ambassador” (Scott 1972b:4). By blending domesticity, delivering sociability, and engaging with local art, culture, customs, socialites, and the media, these women underscored the ‘softness’ of soft power and animated the changing face of American diplomacy.

References

Bakhmetyeva, Tatyana. 2002. “Diplomacy in the Woods: Nature, Hunting, Masculinity, and Soviet Diplomacy under NS Khrushchev.” Diplomatica 4(2): 269-305.

Brinkley, Douglas. 2019. American Moonshot: John F. Kennedy and the Great Space Race. New York: Harper Collins.

Flynn, John. 2024. “Summit Diplomacy: US-Soviet Mountaineering Exchanges, 1974–1989.” The International Journal of the History of Sport 1: 1-28.

Gallarotti, Giulio M. 2011. “Soft power: what it is, why it’s important, and the conditions for its effective use.” Journal of Political Power 4(1): 25-47.

Morin, Ann Miller. 1994. “Do women make better ambassadors.” Foreign Service Journal 71(12): 26-30.

Muir-Harmony, Teasel. 2020. Operation moonglow: A political history of Project Apollo. London: Hachette UK.

Penler, Alexandra. 2023. “The quiet diplomats: American diplomatic wives and public diplomacy in the Cold War, 1945-1972.” PhD diss., London School of Economics and Political Science.

Pyzik, Agata. 2015. “Warsaw’s Palace of Culture, Stalin’s ‘gift’: a history of cities in 50 buildings, day 32.” The Guardian, May 8. Warsaw’s Palace of Culture, Stalin’s ‘gift’: a history of cities in 50 buildings

Rogers-Cooper, Justin. “Rethinking Cold War culture: Gender, domesticity, and labor on the global home front.” International Labor and Working-Class History 87 (2015): 235-249.

Rothman, Steven B. 2011. “Revising the soft power concept: what are the means and mechanisms of soft power?.” Journal of Political Power 4(1): 49-64.

Scott, David. 1972a. “Apollo 15 Visit to Poland and Yugoslavia.” March 08. DRScott_Memo to Astronauts on A-15 Poland-Yugoslavia Visit, Digitized File, Canvas SOC SOC 585-4, Emory University.

Scott, Lurton. 1972b. Speech given at “A Luncheon in honor of Mrs.David Scott” for the wives of the doctors attending the American Academy of Ophthalmology and Otolaryngology Convention in Dallas, TX, 27 September. 1972 LurtonScott – Speech TRANSCRIPT. Digitized File, Canvas SOC 585-4, Emory University.

Shimazu, Naoko. 2014. “Women Performing “Diplomacy” at the Bandung Conference of 1955.” Pp. 34-39 in Bandung at 60, edited by Darwis Khadori. Indonesia: Pustaka Pelajar.

Towns, Ann E. 2020. “‘Diplomacy is a feminine art’: Feminised figurations of the diplomat.” Review of International Studies 46(5): 573-593.

Uri, John. 2021. “50 Years Ago: Apollo 15 Astronauts Post Mission Activities.” NASA website, Sept 01. 50 Years Ago: Apollo 15 Astronauts Post Mission Activities – NASA